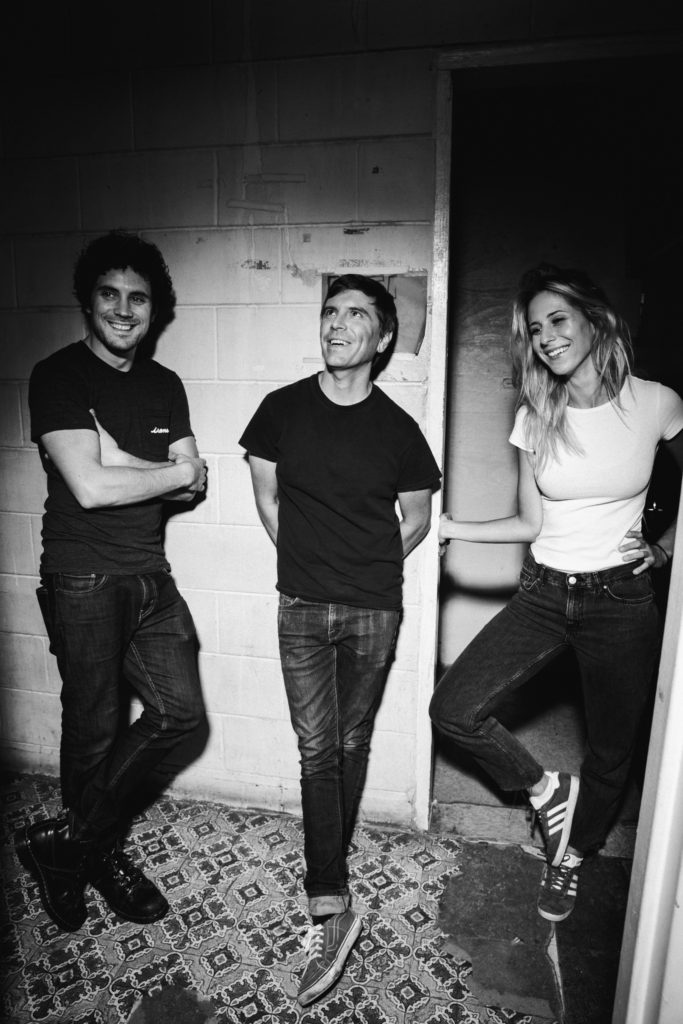

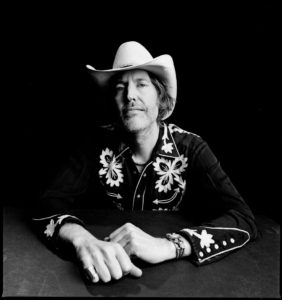

A conversation with singer/guitarist Jimbo Mathus

By Blake Ells

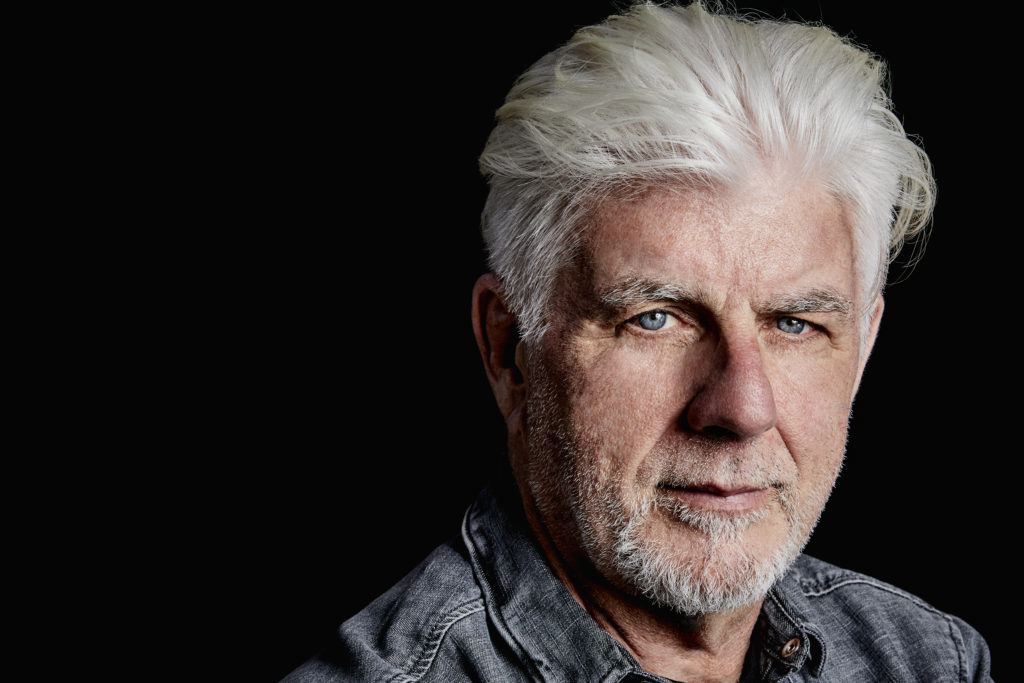

Jimbo Mathus moved back to Taylor, Mississppi around 2003 and he’s been a big part of Oxford’s music community since, making frequent appearances on Thacker Mountain Radio. He grew up in Corinth, just south of Jackson, Tennessee and just west of Muscle Shoals, Alabama. When he was 16, he recorded with legendary Florence native Sam Phillips in Memphis. He studied at Mississippi State before leaving for Chapel Hill, North Carolina; he’d spend a decade there and begin a music career before moving back home. So he has a bit of a relationship with the South.

He talked about that relationship and about recording with Phillips. He talked about Buddy Guy and Mississippi State and Ole Miss and Memphis and W.C. Handy, too.

Birmingham Stages: How did end up recording with Sam Phillips at 16-years-old?

Jimbo Mathus: Well my shop teacher paid for it. We had a little rock and roll band, and he said he wanted to be our manager. [laughs] It was one of those things, man. He didn’t know what the hell he was doing; we had some 45s printed up and sold them at the sock hops and shit.

He opened up the Memphis phone books and looked up studios and that was the one he saw. He didn’t know Sam Phillips from Abe Lincoln. That’s just the one that was open and the one that we went to—I didn’t even realize until years later where the hell I’d been. Roland James was the engineer and all that. I didn’t realize all that shit until years later.

Birmingham Stages: Did you accidentally meet Sam when you had that session?

JM: No, because we were just a session for hire. We probably had half a day—two or three hours. But I do know that Roland James was the engineer, because he was the house engineer then.

Birmingham Stages: When you recorded that record, were you already writing your own songs or were you performing covers?

JM: I was just starting to get hip to the concept of writing my own songs. I didn’t start that in earnest until I was 17 or 18—about 18.

Birmingham Stages: Did you ever get grief in Mississippi for being a white guy playing the blues?

JM: I didn’t really do it in public; it was just kind of a private thing that I was learning on my own. By the time I started playing blues in public, I had already won a Grammy for the blues with Buddy Guy, so I didn’t catch a lot of grief behind that. [laughs]

Birmingham Stages: How important was his seal of approval and how valuable was the time you spent with Buddy?

JM: Oh my God—it was incredible. I learned so many lessons, man, and when you’re working with somebody like that—you ain’t just learning about the blues, per se, you’re learning about everything. You’re learning about music, handling your business and being a master at what you’re supposed to be doing. I worked with him on and off for five years.

After that experience, I was like, “Well, I reckon I’m a blues guitar player now.” I really don’t have a lot to be ashamed of, so I just jumped on in.

Birmingham Stages: How did you get hooked up with Buddy? How did he get the notion that you might be a blues guitar player when you weren’t really playing in public that way?

JM: At that time, I was in the heyday of the Squirrel Nut Zippers, which had little or nothing to do with what I was doing with Buddy Guy. But some people that had known me in some studios—particularly down at [a studio] down in New Orleans—recommended me for the job because they knew me and they had spent enough time with me to know. Here I was playing a lot of different types of music—including the blues—and they wanted sort of a wild card approach to it; they didn’t want the standard dude anyway.

So it came through word of mouth—the producer called me and he had never heard of me and didn’t know anything about anything pertaining to me. But he said, “Man, you’re recommended.” And he explained the concept to me and I told him I’d be perfect for it and he said, “I think you’re right.” And he hired me. He told me to get down there and that started a whole new path to my life. Pretty amazing.

Birmingham Stages: How did you first meet Luther and Cody Dickinson and what’s that relationship like now?

JM: I met [the Dickinsons and their father, Jim] at the same time. That was in Memphis at a place called Barrister’s; it was a club—one of the only times that the Zippers ever played in Memphis back in the day. [Luther’s] band Gutbucket was the opening act. We were just passing through town; I didn’t know anything about Luther, but I knew about Jim; I knew about his history and what he’d done and who he’d worked with and all that kind of stuff. Luther and I hit it off big time and started communicating and started collaborating almost immediately. And the same for Code-man, but Luther is more of my main collaborator.

I went on to work with Jim—I played on a lot of his records—I think Killers from Space, Jungle Jim and the VooDoo Tiger and he and I became really good friends around the mid ‘90s.

Birmingham Stages: You grew up in Oxford and you went to school in Starkville for a little bit—are you a Rebel or a Bulldog?

JM: I plead the fifth.

Birmingham Stages: So that’s as dangerous of a topic there as it is here?

JM: Hell yes! [laughs] I got arrested in Starkville more times than anywhere else, I’ll say that.

Birmingham Stages: Mississippi deals with a lot of issues related to its image. One that’s been a hot topic in recent years is the state flag. Is that something that you think should be changed or rectified in any way?

JM: Yeah. I think they oughta go back to the old magnolia tree flag. That’s just me.

I changed my mind about that over the years. And that’s the way I feel about it. Because that rebel thing—ain’t no way to spin that in the modern world—just drop it. It’s more trouble than it’s worth.

Birmingham Stages: Squirrel Nut Zippers was a lot different than everything else you did. Was that deliberate?

JM: Well, it was the first thing I was known for, so most people think everything I’ve done in the 20 years since then was different from that. It’s a whole different genre of art; it’s based on other things than the rest of my career, like honky tonk music, blues, rock and roll, psychedelic, swamp pop, gospel, all the other stuff. It’s not early American jazz, vaudeville, cabaret, calypso and all that other stuff. It’s just two different things. It wasn’t on purpose. It was by accident; I wanted to learn everything I could about music, art, everything that had gone down to lead up to where I was at in my life at that time. So I set about learning all about it and it was a product of me figuring out how to play W.C. Handy; how to play jazz. So naturally, as a writer, when I learned the moves, I started writing in that genre. And that happened to take off; it was really quite an accident that anybody ever heard that kind of thing out of me. It was a wild accident.

Birmingham Stages: I think in a lot of the other things you do, you can hear what geographically influences you. But you can’t with Squirrel Nut Zippers. So was that Handy?

JM: Yeah, it came from people like W.C. Handy, Stephen Foster, Louis Armstrong, “Fats” Waller, Bertolt Brecht. German theater—we had the whole costuming—look and style of theater. And my whole thing was Kurt Weill, Bertolt Brecht—German-type stuff; the calypso stuff—Lord Executor, Roaring Lion—they were like the first rappers, basically. New Orleans has quite a bit of it. That’s where geography comes in.

Birmingham Stages: I guess now that I think of it, Mississippi probably gets a lot of influence from New Orleans and Muscle Shoals and you’re in the middle of that weird molding together of two sounds.

JM: Yeah! And it comes out of Jackson, Tennessee. Memphis is the center of my universe. It pulled from the Delta, it pulled from the hillbilly music, it pulled from Muscle Shoals, it pulled from Tupelo—so Memphis is the geographic center of my music.

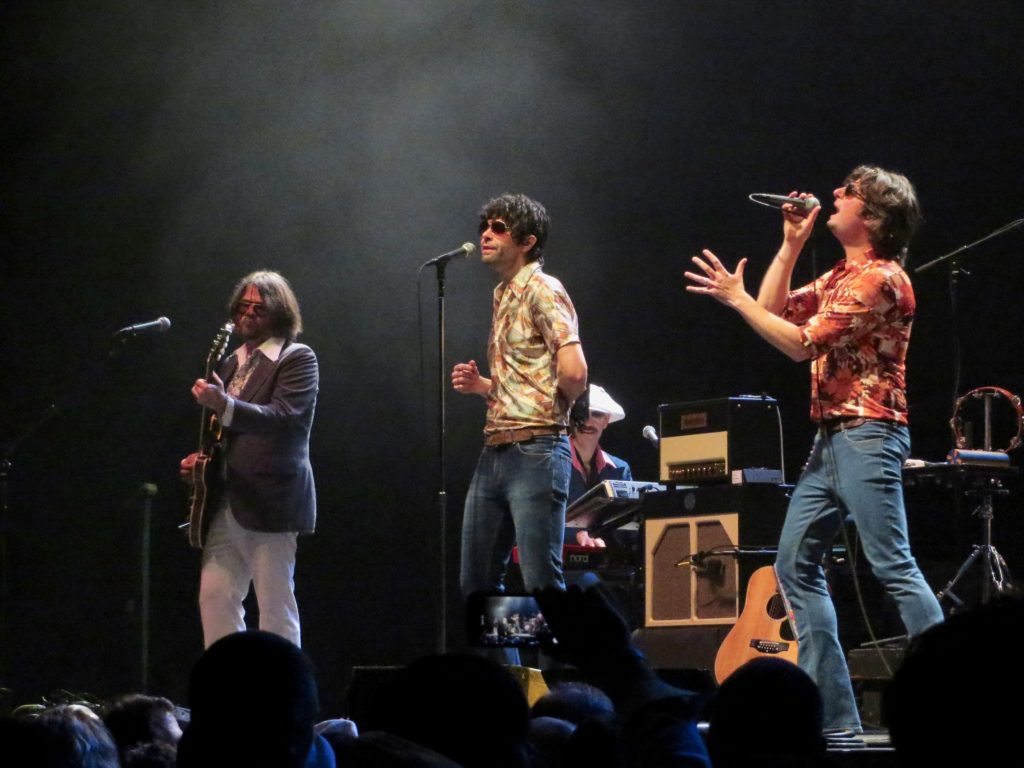

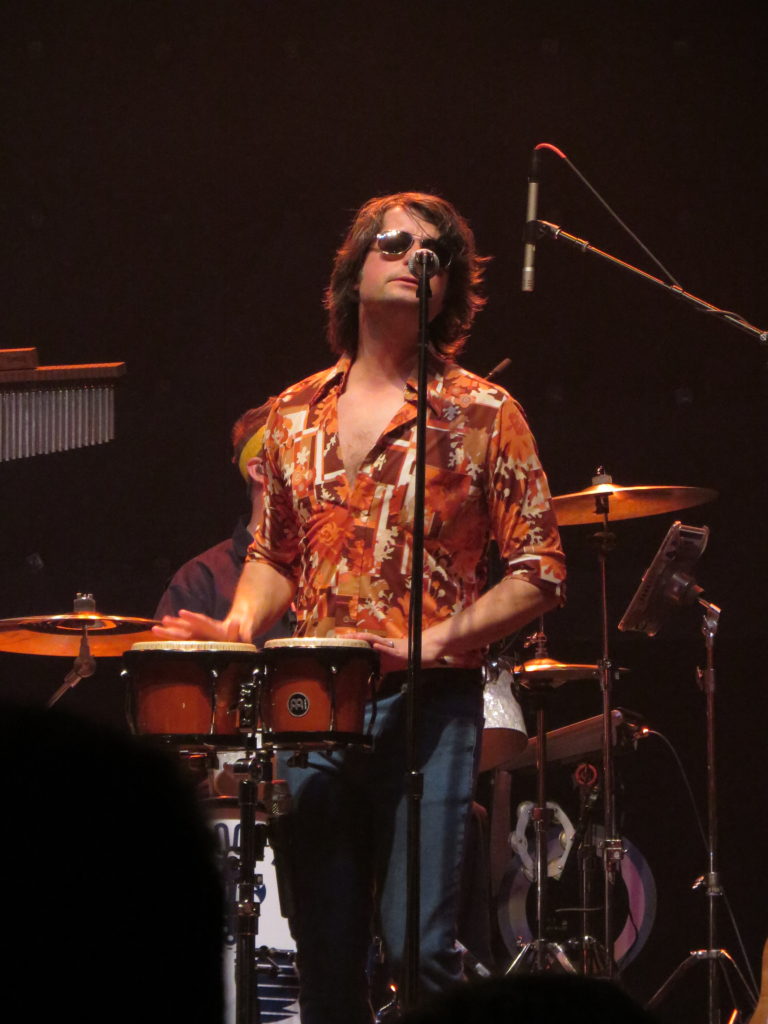

Squirrel Nut Zippers Christmas Caravan comes to The Lyric Theatre on Friday, December 1. Doors open at 7 p.m. Show begins at 8 p.m. Tickets are $28.50-$49.50 and can be purchased at www.lyricbham.com.

mastered it and the artwork was done and I saw his title come up and thought, “Is he playing that old tribe song?”

mastered it and the artwork was done and I saw his title come up and thought, “Is he playing that old tribe song?”