By Blake Ells

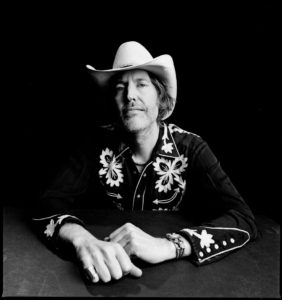

Photo Credits: Alysse Gafkjen

David Rawlings has become a fabric of the Americana community, notably announcing his presence at the beginning of Ryan Adams’ seminal debut album Heartbreaker in 2000. He’s since worked with Old Crow Medicine Show, Ani DiFranco, Robyn Hitchcock, Bright Eyes and Sara Watkins among others. His own Dave Rawlings Machine has featured his longtime collaborator and partner Gillian Welch, Willie Watson, Paul Cowert, Brittany Haas and occasionally former Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones over two records and the touring that followed for nearly a decade. And while the band is the same, they decided to release the latest effort under his name alone.

He talked about that decision before returning to Birmingham. He also chats about coincidentally writing a song that shared a title with a song by Jason Isbell, he offered a look into his songwriting process and he explained the argument with Ryan Adams concerning Morrissey.

Birmingham Stages: Why was it important to you this time to release the album as “David Rawlings?”

David Rawlings: After we had this collection of songs together and we recorded it—we were just starting to understand what we thought it might be, we’d played it for a few people—and we were trying to figure out what to title the album, it just felt—for whatever reason—that the “Dave Rawlings Machine” name didn’t fit very well on it. And a couple of people had asked, “Are you gonna put this out as the Machine? Are you gonna do something different?” And that hadn’t really occurred to me to do something different, but I knew that we were struggling to come up with a name a little bit.

We thought of the Poor David’s Almanack title and it just felt like if we were going to do that, we had to just call it “David Rawlings.” We wrung our hands about it a little bit; we weren’t really sure. You always think about—if you’re in the car and a song comes on and you see the song title and you see your name—we spring from a tradition of singer-songwriters and people just play under their names. So the band is kind of a different thing—if you see “Dave Rawlings Machine,” you’re maybe not thinking the music is gonna sound like what it sounds like. But there’s something about Neil Young or Bob Dylan; Richard Thompson or Paul Simon; all of these musicians that I grew up listening to, that’s what you did.

So we thought, “Well, let’s go ahead and do that. It’s not gonna confuse too many people.” [laughs]

Birmingham Stages: Does that effectively dissolve “the Machine” or is that something you may go back to?

DR: [laughs] No, we’re still playing with the same people. It was just a name, you know? We did more touring as “the Machine,” and we thought about leaving that as the touring name, but that seemed like it might be more confusing than it was. In the end, “Gillian Welch” has always been the name we’ve used as our sort of band name, and we thought, “Well, ‘David Rawlings’ can be the same thing.” And it’s just simpler.

Birmingham Stages: How did you and your friend Jason Isbell react when you realized that you’d both written a song titled “Cumberland Gap?”

DR: I didn’t know—I guess—until I saw his pop up on the radio. I think his came out first—ours wasn’t out yet—we had  mastered it and the artwork was done and I saw his title come up and thought, “Is he playing that old tribe song?”

mastered it and the artwork was done and I saw his title come up and thought, “Is he playing that old tribe song?”

We got a couple of good laughs about it. “Cumberland Gap” is up for American Roots Song for the Grammy against “If We Were Vampires,” and he like, “Man, I wish it was “Cumberland Gap” against “Cumberland Gap.” [laughs] “So we could let people vote on which one is better. But I guess yours wins because yours is up for a Grammy and mine isn’t.” [laughs]

I don’t think that’s true. I really like his. You know sometimes, it makes you wonder about the cultural zeitgeist and what’s popping around in people’s heads and why. I have a clear memory of how that title popped into my head—obviously I know the traditional song—but I was working on that melody and working on that song and I guess I had a couple of lyrics that I wanted to put in the chorus, but I didn’t have a title; I didn’t really know where the song was gonna go. “Cumberland Gap; a devil of a gap” literally just popped out of my mouth.

I wasn’t thinking—sometimes you just open your mouth and see what you say—and that’s what I said. It came from nowhere as much as anything, but as soon as I talked to Gillian about it and she got her mind around what kind of story that made her immediately think of and we started developing that story and working on it, we were really happy about it. There seemed to be a real feeling of a journey or of exploration or of freedom or frontierism; all of those feelings were in the music and in the melody for me. So it was easy to focus those thoughts around something as important as the Cumberland Gap was in history—a gateway to the west back then.

Birmingham Stages: All of these songs in this collection have an extremely timeless quality about them—they feel like they were written 30 or 40 years ago, and I imagine they were all written fairly recently, especially a song like “Airplane.” How do you do that when you’re writing songs? Where do you draw that timeless quality from?

DR: “Airplane” is something that Gillian had started—as far as these songs, that was maybe the one that got started the longest ago. That was maybe three or four years ago, Gill had written the top part of that chorus—which was just beautiful—and we always liked it, but we didn’t really finish the chorus the way we wanted to and it didn’t connect to much else of a story, so it was something she’d sung some; we’d thought about it—it probably hung around a couple of weeks, but eventually, it just kind of stayed in my head as this cool thing. In the spring of 2016, I was sitting around and I started playing that and I had a couple of ideas—and it did kind of connect to songs from the 1970s—that thing that has a Southern feeling to them. I started to hear it that way; it wasn’t how it initially was. So I thought, “In a song like that, I’d want those chords to stay pretty much the same the whole song and write a verse that connected to it; that had kind of a different feeling, but was over the same music.” And I managed to wrap up the chorus in a way that we thought was cool.

So I think sometimes it’s good to have written a little piece of music and get some distance on it. Then you come back and you view it through another lens and you think about it relative to some different music and then you can kind of shape it a little bit to use some of the things that those songs use to make you happy.

In songwriting, you need to kind of be inside yourself, finding things that work; and then outside yourself at the same time, looking back at what you’re doing and thinking, “Well, how would this make me feel if I was just listening to it?” So when you say, “How do you do that?” it’s being able to toggle the switch between wanting to express yourself, but also wanting to use things that you’ve heard or feelings that you’ve heard that have moved you; trying to use those same kinds of devices.

I’m glad that it hit you well.

Birmingham Stages: You and Gillian have always backed one another on tour—how do you balance that at this point in life? Do you make a conscious decision that, “This is going to be a Gillian Welch year” or “This is going to be a David Rawlings year?”

DR: The business has more to do with how it ends up than we do, because if we could set it up where we played a few shows with her name on it and then a few shows with my name on it; that we could records some songs one day and the other songs another day, we’d probably be happier with it. Maybe the hardest thing about trying to do both of our music is that you kind of have to do it in chunks. If you want to think about the most natural way it is, we’re sitting in the room playing songs—she’ll sing a couple, I might sing one, she’ll sing one, I might sing a couple—that’s kind of how it is; it’s just music. We both like singing lead and we both like singing harmony.

She’s such a great singer and writer that it’s easy to do; this record we just made, it was a struggle. Because we thought, “We just made a record with my name on it, do we really want another one?” and we thought, “Well, these songs just popped up, faster than we’ve ever done anything.” And we recorded them—we budgeted seven or eight or nine days to record—and really ended up getting most of it in a couple of days. So it was all of a sudden there and we just put it out into the world.

From the outside, the impression is that we’re focusing on that, but the truth is, since we’ve been doing this, we’re just working on new songs and trying to get something together so we can get our next recording out as soon as we can.

When you say, “How do you balance it?”—well, you just get up every day and start thinking about what you want to happen and try to make it happen. Maybe someday we will be able to do shows where we’re just swapping off like we would normally do.

Birmingham Stages: How did Ryan Adams’ argument with you concerning Morrissey begin?

DR: It’s confusing if you listen to the recording; it sort of seems like we’re talking about “Suedehead,” but we were talking about “Hairdresser on Fire.” I had gone looking for that song on Viva Hate the night before—I had a cassette of Viva Hate—and on the back of that cassette, the way the text lays, “Hairdresser on Fire” is on a line that gets kind of obscured by the way the plastic kind of goes together. The plastic is round and it refracts the light so you don’t see that line of text; so I’m looking at Viva Hate thinking, “I thought that was on here” and it was like, “That’s not on here!”

I knew it was on Bona Drag, because I listened to that a little more. So I grabbed Bona Drag and I listened to it and we were talking about “Hairdresser on Fire” and he was saying it was on Viva Hate and I was saying it was on Bona Drag. And I was like, “No, I just looked.” And that’s how it started. And of course it was on both. So there was no real definitive winner of the bet.

It cracks me up. That was a lot of fun and we were talking with Ryan; he’d lived in Nashville for a minute then and we used to get together and jam and party and have a good time. We weren’t even really planning on going and working on that record, but he started doing it at Woodland and he called us up and asked us to come in a play for a few days and we ended up playing a lot of the record over three or four days. It was just all loose, and I thought it was really smart that they started the record with something that showed just how casual the sessions were. I think that’s a really powerful record and a great collection of art and a great collection of songs. And I think it’s a real testament to somebody like Ryan whenever you can have done that quality of work, but keep that kind of spirit on the record and not make the record itself too precious.

I talked to somebody the other day that mentioned how different that record sounded in the face of whatever else was coming out at that moment—I think I said Stone Temple Pilots or something—you know what I mean? For people that wanted that kind of feeling or that kind of music, it was a real landmark. We were just proud that we got to be part of it.

David Rawlings will perform at the Lyric Theatre on Wednesday, January 24 at 8 p.m. There is no opening act listed on the bill. Tickets start at $36 and can be purchased at www.lyricbham.com.